05 November 2024

|

Netrunner is a fantastic example of when a game ends, but its community doesn't let it. Null Signal Games not only revived Netrunner, but have made it a passion project, introducing the game to new audiences and new heights.

Written by Tim Clare

What is Netrunner?

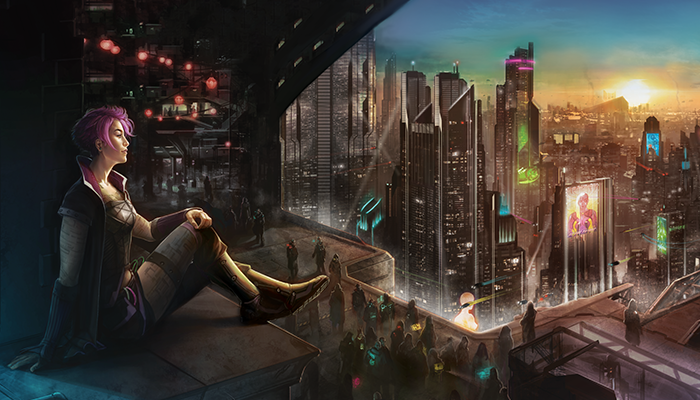

Netrunner is the card game that Magic: The Gathering designer Richard Garfield made next. Whereas Magic is a pitched battle between interdimensional superbeings, right from the start Netrunner was something altogether grimier and more cerebral. If Magic is two opposing battlelines smashing into each other while heroes and villains duke it out with thunderbolts and fireballs, Netrunner is rain-slicked alleys, wiretaps, and a dagger slipped between the ribs.

Netrunner History

The original Netrunner, released in 1996 by Wizards of the Coast, was set in a cyberpunk future that accelerates contemporary dilemmas and injustices to queasy, dystopian extremes. Megacorporations own everything – the media, the global workforce, even the government. Surveillance is ever-present, inequality is extreme, environmental disaster impacts the worst-off and the thirst for cheap consumer goods fuels rampant – albeit discreet – exploitation and outright slavery. It was a charmingly-unbalanced affair that rapidly petered out.

It returned in 2012 as Android: Netrunner from Fantasy Flight Games (FFG), set in the world of the divisive cult classic ‘adventure boardgame’ Android. While the core of what makes it great was there from the beginning, the new edition significantly improved on the original, and found an enthusiastic – albeit, by Magic’s elephantine standards, small – player base.

How to Play Netrunner

Unlike Magic, the rereleased Netrunner was – and is – an LCG rather than a CCG. That is, instead of amassing cards for your deck through random pulls in booster packs and the second-hand market, cards were printed and released in non-random sets. Except for special alt-art versions of cards given away at events, every player theoretically had equal access to an identical card pool.

The basic setup is asymmetric – each player has two decks, Corp and Runner. Corps are the aforementioned huge, multinational, multiplanetary conglomerates, working on various schemes – called ‘agendas’ – to increase their profits, stymie their rivals and cement their dominance. Runners are the hackers trying to break into Corps’ sprawling servers, hoping to steal those agendas to sell for a profit, expose the rot at the heart of society, or just to see if it can be done.

You take it in turns playing as Corp and Runner, racing to be the first to either score or steal seven agenda points. The Corp can also lose by decking out – if they have to draw a card and their draw pile, aka ‘R&D’, is empty – and the Runner loses if they ever have to discard a card and their hand is empty, representing their brain and/or body getting blown to smithereens by the Corp’s countermeasures, which can be as subtle as security protocols frying the Runner’s delicate neural interface, and as crude as sending heavies round with guns.

The Corp gets to build servers by playing cards face down. These might include assets, which make you money – almost everything in the game, for either player, costs credits to play – agendas, which you need to spend money and turns advancing in order to score them, or traps – cards which, if the Runner accesses them, can drain the Runner’s coffers, end their turn early, even kill them. The Corp can protect its servers with ICE (Intrusion Countermeasures Electronics), layers of security which the Runner can only neutralise by installing and using specialised breakers.

The game, then, usually plays out as a race, the Runner rushing to get their full suite of breakers set up before the corp can establish an econ engine or score out seven points worth of agendas. But since the corp almost always plays its cards face down, and since activating those cards – turning them face-up or ‘rezzing’ them – almost always costs credits, the Runner is often incentivised to start hitting servers before they’re entirely ready.

After all, the Corp might not have enough money to Rez ICE over every server. Maybe you can feint a run on R&D, forcing them to decide whether to risk you accessing their next card – potentially trashing a key combo piece or stealing an agenda – then, once they’ve spent precious credits protecting it, make your real assault on HQ (the cards in their hand). But then, if you get in too easily… was this the Corp’s plan all along? Are you walking into a trap?

Whilst I love Magic, but I’m going to be outrageously partisan and say that Netrunner is the better game. It exploits asymmetry and hidden information to create a compelling, tense showdown where you can squander an apparently assailable position in a single blunder or claw a win from almost-certain defeat by playing to your outs.

Netrunner Ends

The constant shell game of testing defences and switching targets, of critical turns and lulls as you regather your resources, is what makes Netrunner so compelling. But after 2012, as the game expanded, it began running into many of the problems that plague games with growing card pools. With each new release, the barrier to entry for new players got more and more expensive. You couldn’t go to your local game store’s Netrunner night with cards from the core set and join in – the difference in power level was way too high.

Fantasy Flight Games began releasing new packs on an ever-faster cycle, so players felt like they’d barely adjusted to new, meta-warping cards before yet another set dropped. Power creep was inevitable under these circumstances, exacerbated by what felt like some poorly-playtested card designs. Many players felt like FFG were prioritising short-term profit over the health of the game, and it didn’t come as a huge shock when, in 2018, FFG announced their support for the game was coming to an end.

And that, I – and most other Netrunner players – assumed, was that. Enter Null Signal.

New Netrunner with Null Signal Games

“FFG put out the article, entitled Jacking Out, explaining that they would no longer be running the game,” I was told by Serenity, who was VP of Engagement at Null Signal for five years. “That hit the community pretty hard. We lived, [and] breathed Netrunner” But after a couple of days, as the shock wore off, some players realised: “Wait. We don’t have to put up with it. We can just… keep making Netrunner ourselves?’

Count me amongst the sceptics who, when news of a fan-led continuation of the game first broke, thought it was a well-intentioned but ultimately doomed exercise in refusing to accept the inevitable. How could a few plucky nerds scattered across the internet match the might of a well-funded international corporation?

Apparently, I’d missed one of the game’s central lessons.

Null Signal has not only kept the game going, but, with a revised core set, a much slower release schedule, and multiple play formats (allowing play with a limited card pool), Netrunner has never been more fun. It’s run as a nonprofit collective, by and for fans.

“We have people working on this who love the game – not to say that people at FFG didn’t, I’ve spoken to several of them, but they had profits and shareholder value to worry about. We don’t. We can afford to delay a pack release if we feel something isn’t up to quality,” Serenity said of it. Occasionally people will complain that, with slower releases, the meta gets solved, but Serenity says: ‘There’s always a deck that comes out of left field, gets dropped at a regional and boom!”

Under Null Signal’s watch, the player base has grown more diverse, beginning to catch up with the diverse characters featured in the game. Netrunner is unlikely to ever enjoy the colossal success of Magic, Pokémon or Yu-Gi-Oh, but if you want an exciting, tactical, often just very funny card game experience, there’s never been a better time to jack in.