01 January 2020

|

Fighting Fantasy helped give rise to games where every decision counts – and every player can experience a different story. Your adventure awaits!

"Along the far shore of the lake stands a grand city, like none you have ever seen,” writes option 179 of board game Tales of the Arabian Nights’ vast Book of Tales. “Within one building you hear anguished moans; from another, a woman crying,” it continues. Dare you enter?

Decisions and consequences are a key part of gaming, woven into the thread of roleplaying and story-driven games. Even off the table, recent times have shown an upsurge of interest towards traditional interactive fiction formats, whether it’s choosing to drop LSD and surf time loops in branching Netflix TV adventure Black Mirror: Bandersnatch or tweeters playing as fictional personal assistants to Beyoncé in a viral Twitter thread – selecting her breakfast salads and whatnot.

The format’s origins go as far back as the ‘40s. A precursor to today’s interactive narrative is short story ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’. Written by Jorge Luis Borges in 1941, its protagonist finds a labyrinthine novel.

“The book is a shapeless mass of contradictory rough drafts,” the main character laments. “I examined it once upon a time: the hero dies in the third chapter, while in the fourth he is alive.”

The short story’s imagined book has all the cursed enigma of a cosmic horror tome but is, in essence, an interactive fiction title.

These murmurings evolved further into distinctly less mystical multiple-choice maths quiz The Arithmetic of Computers in 1958. 11 years later, lawyer Edward Packard told his daughters a bedtime story. He asked them what they wanted the main character to do, then created different outcomes based on their decisions.

Over time, his tales morphed into book The Adventures of You on Sugar Cane Island, which was published in 1975 following multiple rejections. That title led to a deal with Bantam Books, and the birth of the Choose Your Own Adventure series. Between 1979 and 1998, the series shifted 250 million books and spanned over 150 titles.

They were written in second-person, and each page offered a new choice (or death) accessible via different page numbers. You could be a spy, astronaut or, in later instalments, a literal shark.

Endings reached up to 44 per book, and a few featured trick finales. For example, Inside UFO 54-40 could only be completed via cheating, while the aptly-titled The Race Forever could indeed never end.

Coming out Fighting

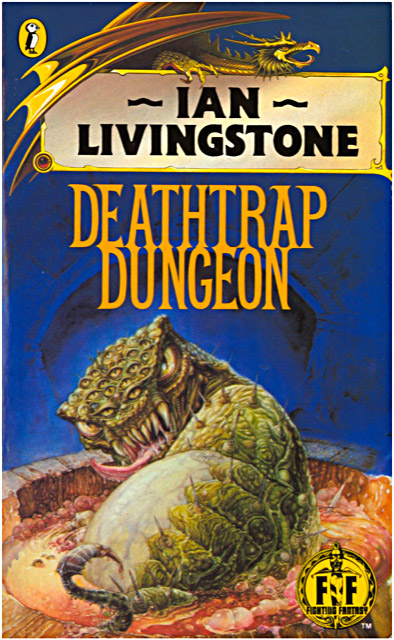

At the same time, in the UK a new breed of interactive adventure – steeped in fantasy books and Dungeons & Dragons – began to take hold. In 1982, Games Workshop co-founders Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone wrote The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, the first in the ongoing Fighting Fantasy series.

Unlike the Choose Your Own Adventure stories, the Fighting Fantasy titles in which “YOU are the hero” included a dice-based roleplaying element. You could also acquire items, and roll stats to create a simple character at the start using six-sided dice. Combat was determined by your rolls augmented by the stats.

“First, it was a new concept: a branching narrative with a games system attached to it,” says Livingstone, regarding the challenges inherent to writing The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. “Second, we had to design a games system that was not too complicated and worked in book format. Third, we had to write a thrilling fantasy adventure with multiple choice and multiple endings. Fourth, we had to split the task of writing it.”

In addition, Livingstone and Jackson created Warlock’s infamously gruelling ‘Maze of Zagor’, which must be circumvented to reach the book’s titular warlock – and his riches.

“With hindsight, the maze in Warlock was a bit tough to navigate, but it certainly became a talking point!” Livingstone says. “The important thing for us was to draw a map to keep track of the routes and encounters in the adventure, and keep a record of the paragraph numbers on a flowchart.”

Fighting Fantasy presented worlds stranger then the CYOA series, with bloody battles and the near-constant threat of death. They took you to far-off places like the Forest of Doom, and then expanded out into the stars and savage cities. Popular during pre-home computer times, they must have felt uncanny to some young readers, like their first introduction to death. So compelling, yet often cruel.

“I was obsessed with D&D in the 1970s and always believed that fantasy roleplaying could attract a wider audience if it was made more accessible,” says Livingstone, regarding the series’ influences. “Replacing the dungeon master with a book offering a multiple-choice quest seemed like a good way to do it, but adding a simple combat system to increase drama and tension.

“I was a huge science-fiction and fantasy book reader and always wanted to experience the adventures of the main characters in the books.”

Livingstone still draws out the Fighting Fantasy story branches by hand, making vast narrative maps numbered 1 to 400. However, the text is typed – not penned – these days.

“I start by devising what I hope is an intriguing quest for the reader,” he says, outlining the process behind the 72nd Fighting Fantasy title, Assassins of Allansia. He plans where the adventure is going to take place, its main protagonist, and designs the overarching storyline. Writing the book itself is an iterative process, as Livingstone works on several branches of the story simultaneously.

“There’s a lot of going back and forth,” he says. “For example, when I include a locked chest in a room, I have to go back in the story and put a key somewhere where readers can find it.”

Overall, the biggest challenge is ensuring all the branches weave in and out of each other correctly. Players shouldn’t get stuck in a loop, but also need to arrive at certain crucial points for the sake of story.

Livingstone also considers balancing key, and runs playtests to ensure that the monsters aren’t too tough to beat without cheating via the “five-fingered bookmark”.

“Above all,” he concludes, “there has to be a compelling story to make the adventure captivating and satisfying. For me, the fun is trying to lure people to their doom!”

TURN THE PAGE

The essence of Choose Your Own Adventure and Fighting Fantasy translated into board games, such as 1985 release Tales of the Arabian Nights. Ostensibly a simple game of making it around a board as any one of legendary heroes Sinbad and Ali Baba, players roll dice and pull event cards. However, Arabian Nights also includes the far-reaching Book of Tales – a weighty tome featuring 2,600 paragraphs numbering choices and outcomes. It works in tandem with the game’s ‘reaction matrices’ – arcane tables that bridge out onto the stories contained within the tome, navigated via a heady mix of dice rolls, choices and location. It’s a wild, often violent ride: you can be crippled by a Sultan, shamed by old ladies and ensorceled by storms. You can also garner untold riches.

Beyond Arabian Nights, there are countless board games that include consequence-based story-telling mechanics. The Choose Your Own Adventure series spawned House of Danger last year, a co-op card game set inside a haunted house based on the book of the same name. Ambitious survival-exploration game The 7th Continent, meanwhile, used its own CYOA-inspired ‘choose your own path’ system involving almost 1,000 numbered cards to offer players an entire land and numerous mysteries to uncover during their quest to lift a curse – single playthroughs could last for well over a dozen hours. And not unlike Arabian Nights, harrowing civil-war simulator This War of Mine: The Board Game features the Book of Scripts, which includes over a thousand possible story events, plus characters.

Beyond this, legacy games – where actions permanently affect an ongoing game world – incorporate interactive fiction elements. For example, the action of sprawling RPG dungeon-crawler Gloomhaven takes place mostly on a hex combat grid. But, in-between missions, players are presented with branching story decisions that affect both the town of Gloomhaven and their characters’ own individual paths. Or Pandemic Legacy, which adds an ongoing storyline to the popular strategy game. You open black boxes, filled with chips and other new elements, and these create unique conundrums. Furthermore, any social disintegration caused by your actions and decisions is made permanent by stickers applied to the board and instructions to tear up cards made inaccessible by your choices.

Beyond this, legacy games – where actions permanently affect an ongoing game world – incorporate interactive fiction elements. For example, the action of sprawling RPG dungeon-crawler Gloomhaven takes place mostly on a hex combat grid. But, in-between missions, players are presented with branching story decisions that affect both the town of Gloomhaven and their characters’ own individual paths. Or Pandemic Legacy, which adds an ongoing storyline to the popular strategy game. You open black boxes, filled with chips and other new elements, and these create unique conundrums. Furthermore, any social disintegration caused by your actions and decisions is made permanent by stickers applied to the board and instructions to tear up cards made inaccessible by your choices.

Interactive fiction in games has morphed from the matrices of Arabian Nights to the secret boxes and cards of Gloomhaven and Pandemic Legacy. Before that, it lingered in the hypertext and page of Choose Your Own Adventure and Fighting Fantasy books, weaving stories of sorcery and space. Regardless of the format, all interactive fiction moves in those same vast, unseen narrative webs known only to their creators.

This review originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Tabletop Gaming. Pick up the latest issue in print or digital here or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.