19 August 2024

|

Codenames designer Vlaada Chvátil – if that is his real name – tells Owen Duffy the secrets behind the board game hit that you can find in everywhere from Waterstones to Tesco. Codenames may have a place on our shelf, but what was the process to get the game there to begin with?

Written by Owen Duffy for issue 7 of Tabletop Gaming magazine

Codenames has become one of board gaming’s greatest hits. Critically acclaimed and massively popular, it’s been translated into over 30 languages, racked up huge worldwide sales and received the hobby’s highest accolade: the 2016 Spiel des Jahres, or Game of the Year award.

All of this success might be enough to satisfy some designers, but not Codenames’ creator Vlaada Chvátil. Far from resting on his laurels, he’s been taking the game in new directions and making some big plans for it and other upcoming releases from his design studio, Czech Games Edition.

Tabletop Gaming spoke to Chvátil to find out about his life in gaming, and to learn the story behind one of the tabletop industry’s biggest breakout hits.

Related article: What is the Spiel Des Jahres?

![]() Codenames Design Origins

Codenames Design Origins

Ask a few game designers about their earliest tabletop experiences, and you’ll hear the same influential titles mentioned again and again: Dungeons & Dragons, Cosmic Encounter or perhaps the classic 1980 empire-builder Civilization. Vlaada Chvátil had a very different introduction to gaming. Born in 1971 in the Czech city of Jihlava, he spent the early part of his life living under Soviet rule.

“We didn’t have access to many board games,” he recalls, “and the ones we had were not that great. Some just involved pure luck with no element of skill, and none of them had any kind of epic feeling to them.”

While games, like other western commodities, were hard to come by, Chvátil still managed to encounter one traditional family classic.

“We had a homemade version of Monopoly, created by my father,” he says. “We didn’t hear much English at all in the Eastern Bloc back then, so it looked very exotic with all of the street names and stations. Even though it dragged and wasn’t all that interesting, in my memories it still feels kind of special.

“My grandfather also had a very well-crafted original game which I’ve never seen since. He called it Four Lands, and it was a variation of Ludo with fortresses, shortcuts and some sections of the board where you’d move backwards. I felt it worked much better than Ludo, with some really interesting options.”

Chvátil’s main source of fun, though, was the outdoor games he’d play in fields and forests as part of a youth group.

“It was an organisation similar to the Boy Scouts,” he explains, “except it was less strict and organised. Scouting was forbidden in my country back then, but we were a troop of boys and girls who did similar stuff – going to weekly meetings, spending weekends out in nature with tents or sleeping under the stars. Officially it had a socialist ideology, but no one actually cared about that, at least none of the people I met.

“During the summer holidays we’d spend several weeks on a summer camp, and it was such a significant part of my childhood. We had great people working with us, giving us an example of how to be friendly with each other, and preparing games and activities for us.

“We played what we called ‘fighting games’ – usually team games involving capturing flags, hitting one another with paper balls, trying to get through enemy territory without being caught, that kind of thing. Eventually I became one of the troop leaders, and I think the first games I ever designed fell into that category.”

Chvátil was also developing an interest in the nascent field of electronic gaming, and while kids of a later generation would grow up in a world of Atari, Nintendo and Sega, his earliest exposure to video games was markedly different.

“I first met video games in the ‘70s, even before the era of 8-bit home computers,” he says. “I played on a Polish mainframe computer called an ODRA 1305 at the research facility where my mother worked. I’m not sure what it was for; I think it calculated salaries for Czech knitting factories. It was limited to outputting one line of text at a time but, still, I was fascinated.

“I remember playing some kind of space exploration game, and a text-based strategy game called Hammurabi, and based on those experiences I decided that I wanted to learn how to program. For some reason, there was a series of articles in a women’s and family magazine called Kveˇty (Flowers) teaching programming in BASIC, and I wrote my own expanded version of Hammurabi with more classes of citizens, soldiers, natural disasters and stuff like that. I wrote hundreds and hundreds of lines of code in tiny writing in a notebook and it was never run on an actual computer, because at that time I didn’t have access to any.”

Chvátil’s obsession was fueled when he later discovered some of the classic home computers of the ‘80s: the ZX Spectrum and Commodore 64, along with the home-grown Czech computers at his school. He learned to code games for them all and, along the way, decided to study computing at university.

“The truth is, I was never really into computers,” he muses. “I just thought they were a great platform for games.”

Board Games to Codenames

It was at university that Chvátil discovered the tabletop gaming hobby, but his interest in analogue games came by a circuitous route.

“I spent most of my time in the computer room, coding games,” he recollects. “But I also had other hobbies. I was doing historical fencing, and that sort of converted into combative live-action roleplaying (LARP). I was also still working with kids’ groups. I was designing games for them to play.

“I also met some friends at a local sci-fi and fantasy club, and that was when I discovered Dragon’s Lair, a pen-and-paper RPG that was more popular than Dungeons & Dragons here in the Czech Republic. They also introduced me to the world of big board games – the type that you play all day or all weekend long.”

Chvátil was immediately drawn to long, complex, strategic titles. Some favourites included the epoch-spanning History of the World, Avalon Hill classic Civilization and Blood Royale, a game of intrigue and diplomacy between ruling dynasties in medieval Europe.

It wasn’t long before he turned his hand to designing games himself.

“I loved the epic feeling of those games, and it inspired me to make my own,” he enthuses. “So one of the first games I ever designed was for up to 11 people. It was all about multi-dimensional diplomacy, and it played out over many, many hours.

“It might have been a bit crazy, but I guess it was certainly epic.”

In the years that followed, he continued to pursue his design ambitions, and today Chvátil is known as a prolific creator with a massively varied output. His own take on historical empire building, Through the Ages: A Story of Civilization, challenges players to develop their nation’s economic stability, scientific prowess and military might. Now on its second edition, it’s long been ranked as one of the best games ever published by users of the online gaming hub BoardGameGeek. By contrast, his madcap 2007 science- fiction game Galaxy Trucker casts players as intergalactic delivery drivers, battling against the clock to construct implausible-looking space ships and then watching as they’re battered by asteroids and attacked by pirates, limping through the cosmos with most of their important components missing.

Just as the subject matter of Chvátil’s games ranges from serious to silly, there’s also massive variety in the mechanisms that underpin them: from long, complex, strategic titles to fast, fun and sociable lighter games. It’s difficult to think of another designer with such a diverse approach – a fact that he attributes to the wide range of games he enjoys as a player.

“I design what I play, and I play a huge variety of games, from deep strategy to funny party games,” he says.

“What really inspires me is seeing the unused potential in other games. When I see a perfect game I can sit down and enjoy it, but I don’t feel the urge to go and do something similar. But when I think, ‘Hey, this can be done in a much better way,’ or when I see the possibility of combining different elements, or when I have a completely new idea that hasn’t been done yet, it just sparks something and I get excited to make it work.”

‘Making it work’ can be a long and complicated process, he adds.

“My approach varies from game to game. Sometimes I’ll start with a particular game mechanic, or sometimes an interesting theme, but they’re just shards in my mind. Sometimes it takes years before I arrive at the right combination, I don’t really start to work on a game until I have a clear idea about a theme and about the way it’s going to play. I try to imagine what players are going to do, what the final game is actually going to feel like and what makes it interesting. It’s only when a game starts to work in my imagination that I really begin to develop it.

“For heavier games, many months of work follow. The theme is always firmly fixed; I never change it during development. But, mechanically, the development process is full of crossroads. There are questions that can be solved in many different ways, and it’s always the theme that guides me towards answers.

“For lighter games, the process can be much shorter. But still, I always start with theme in mind.”

Codenames' Humble Beginnings

This theme-first approach has seen Chvátil recognised as one of the most creative and talented designers in the tabletop industry. His output over the years has included Mage Knight, a card-driven game of powerful dueling wizards; Space Alert, a real-time cooperative game with players working together to survive dangerous missions in deep space; and Bunny Bunny Moose Moose, a light-hearted game about woodland animals attempting to evade a hunter which has players use their hands to make rabbit ears or antlers on their heads.

While he has produced a succession of highly-regarded releases, 2015’s Codenames has been his biggest commercial success to date. A team-based party game, it divides players into rival groups of spies attempting to make contact with friendly agents, represented by a grid of randomly selected word cards. One player on each team acts as a spymaster, giving a series of clues to help identify correct answers. They use associations between words to guide their players’ guesses, for example: an spymaster attempting to identify the two words ‘Washington’ and ‘Beijing’ could say: “Cities, two.”

With the links between words often not immediately obvious, giving effective clues can take creativity and lateral thinking. It’s a simple idea, and the result is a clever, funny and instantly accessible experience.

“When I was a student I played some word-association games, and I always loved them,” reveals Chvátil. “For several years I toyed around with the idea of building a game around the idea, but it wasn’t until 2014 that I was at a gaming event and I got the idea for Codenames. I made a prototype right away, but I didn’t even have a pair of scissors, so I just tore up a piece of paper and wrote some words on it, drew a grid, borrowed some components from other games – and within a few hours the first game of Codenames was being played.”

The Success of Codenames

Two years later, that idea has grown into a global success, finding favour beyond the hardcore game geek community and making it onto the shelves of major mainstream retailers such as the US superstore chain Target.

“I never expected it to be so successful,” Chvátil admits. “Looking back, I think I underestimated the players. I was surprised by how much it appealed to non-gamers. Even people who don’t normally play board games can find themselves being dragged into a game of Codenames if they watch one.

“I think one of the great things is the way the game tailors itself to the personality of the group that’s playing. I’ve seen silent, thinky games of Codenames with four players giving the best clues possible, or light-hearted sessions with people making lots of jokes. I’ve seen wild disputes between players, trying to analyse the thinking of their spymaster and strategise their way to victory, or family games with parents just enjoying playing with their kids. Different groups play in very different ways, and it’s interesting to see the different clues in games between, say, TV and movie geeks or a bunch of university professors.”

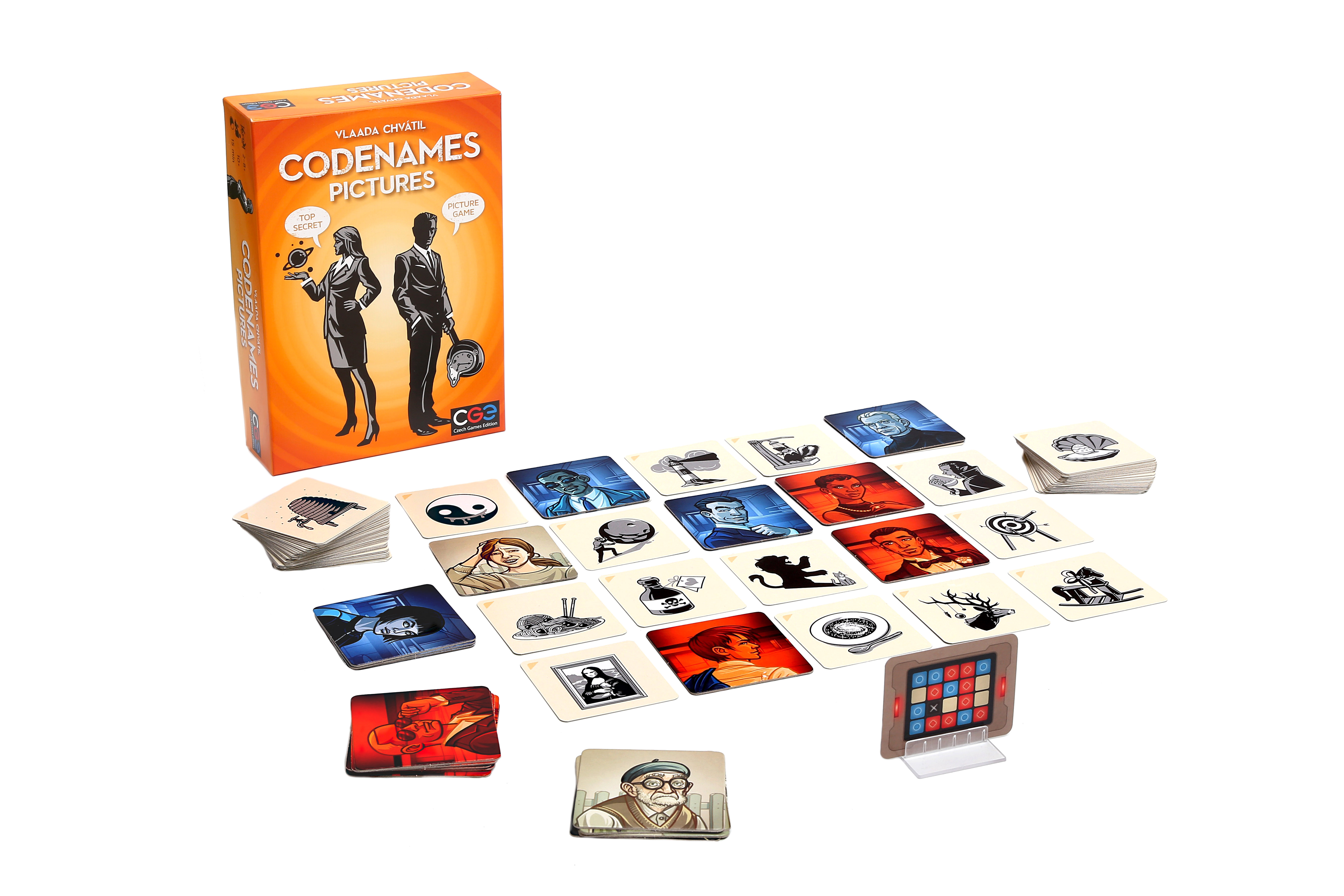

That adaptability has been a key part of Codenames’ appeal, but Chvátil has been keen to explore new possibilities with the game’s formula. The later released Codenames: Pictures introduces a new twist, substituting words for images.

“Codenames is interesting because of the way it plays with language,” he says, “and that makes each localised version slightly different. English contains many simple words with lots of different meanings. German has a great number of complex compound words. Czech is an inflected language that allows subtle hints using many forms of each word. I can only guess how it works in all of the other languages the game has been translated into.

“But we knew right away that pictures would follow. We wanted it to feel different from using words, so every picture in the game has two or more elements. For example, if we just put an image of a pig on a card, it’s not really different from just having the word ‘pig’. But we included a cute little winged piggy bank with a coin being inserted into it. You can use all of these words, all of these visual similarities between cards, and it probably stimulates a different part of the brain.

“During testing we had some people who thought pictures were better than words, and some who preferred words to pictures, and I was glad for that because I didn’t want one game to just replace the other.”

Codenames Online

Another project was a digital version of Codenames. While online play may offer a very different experience, it’s an avenue Chvátil was keen to pursue.

“The idea of remote gaming is an old one,” he says. “People have been playing correspondence chess for over a thousand years. Computers made it much easier, and with tablets and phones it’s become more convenient.

“You can’t recreate the tabletop experience with an app, but with Codenames we hope to offer something else: the chance to play with friends you don’t get to meet often in real life, the ability to play any time you want, a lot of things to explore and achieve.”

It’s not Chvátil’s first experience with app development; the digital adaptation of Galaxy Trucker won high praise for its slick gameplay and visual flair.

“It takes a long time to polish everything, to program a good AI, to add that extra content and make not just a good game, but a great app,” he stresses. “It all takes much longer than we expected. But I believe it is worth it, and our players appreciate it, too.”

Codenames Design Origins

Codenames Design Origins